These new-gen designers and entrepreneurs are making their presence felt in the global fashion scene. We find out how they do it.

Azura Lovisa – Founder of Azura Lovisa

Exploring the rich identities of her heritage, tradition and culture through fashion and design, Azura Lovisa creates an otherworldly wardrobe infused with Southeast Asian and Scandinavian aesthetics. She studied 2D and 3D art alongside academics in an art magnet high school in Miami and later undertook womenswear study at London’s Central Saints Martins. Her work is defined by transcultural flow in a garment with multi-textural finishes, each piece imbued with the touch of the artist’s hand. “The clothes are quite regal, but in a self-assured and understated way – they for those who exist in poetry and power, between cultures and in dreams,” Azura muses.

In a world that is becoming increasingly tech-savvy, why are culture and heritage references important to you?

Because those are the things that make us human. Those are what make us feel. It seems to me the more we become one with technology, the less we feel and the less we understand. So I have chosen to create work that I care about and what I want to cherish in this world.

How different is it to create pieces that explore the idea of gender fluidity compared to those that are more specific?

While my training is in womenswear, I think that most of my silhouettes, with the exception of some of the more fitted styles, work for many different body types. Maybe because I try to avoid looking to Western fashion, which traditionally was very gendered. For inspiration I tend to skew more towards styles of folk dress whose silhouettes often feel more open to interpretation from my contemporary perspective. And the looks that do draw from Western styles, like those that feature tailoring, are naturally suited to all genders. My favourite things to design are sleeves and trousers and as far as I know, arms and legs are not gendered body parts. I just find it very enjoyable to create garments that can live many different lives.

Despite the rise of the fast fashion industry, there is a couture feel to your ready-to-wear collections. What makes you attracted to the style?

One of the things that fascinated me about fashion in the first place was the sense of ritual around it. Rituals of dressing, rituals of celebration through clothing, not to mention the rituals in the fashion industry itself – the runway shows, the cult-like consumption of new collections several times a year. The sociological and psychological aspects of that are really interesting to me. I believe we should be mindful of how we exist in this world. Not so much that we need to care about our image, but care about what we project about ourselves. We can create moments of magic. It’s why I’m so drawn to traditional folk dress – because before the age of T-shirts and jeans, we showed our cultural identity and beliefs and history and pride in who we were through our clothes. And we treasured our clothes, and took care of them, because they symbolised something difficult to put in words. So designing clothes that make an occasion just by wearing them brings me joy. I hope it brings the wearer joy as well, and makes them feel like they are living a beautiful life – not on the surface, but in their heart.

Is there one specific pain point that frustrates you most about the fashion system?

There’s a lot of issues to address, but an important one is the disconnect between understanding the need for sustainable solutions and understanding how this relates to colonial and neocolonial systems of power and oppression that still uphold the system at large. There is a disconnect between caring about the environment and caring about the people in it; humanity still sees itself as separate from nature rather than part of it. The fashion industry mostly looks away from points of tension and denies its own complicity and entangled history with class, race, imperialism, violence, and power. I think younger generations must explore the potentials and problems of fashion as a cultural phenomenon and system of cultural production and affirmation in a way that reveals the interconnected nature of fashion as a record of humanity, infinitely entangled in intersecting systems including but not limited to imperialism and globalisation, capitalism, the environment, ritual and spirituality, tradition vs. modernity, and the writing of history itself.

Is there a lesson that you hope people will learn from the COVID-19 pandemic?

Systems rely on people – change is in our hands. Also, don’t forget to rest.

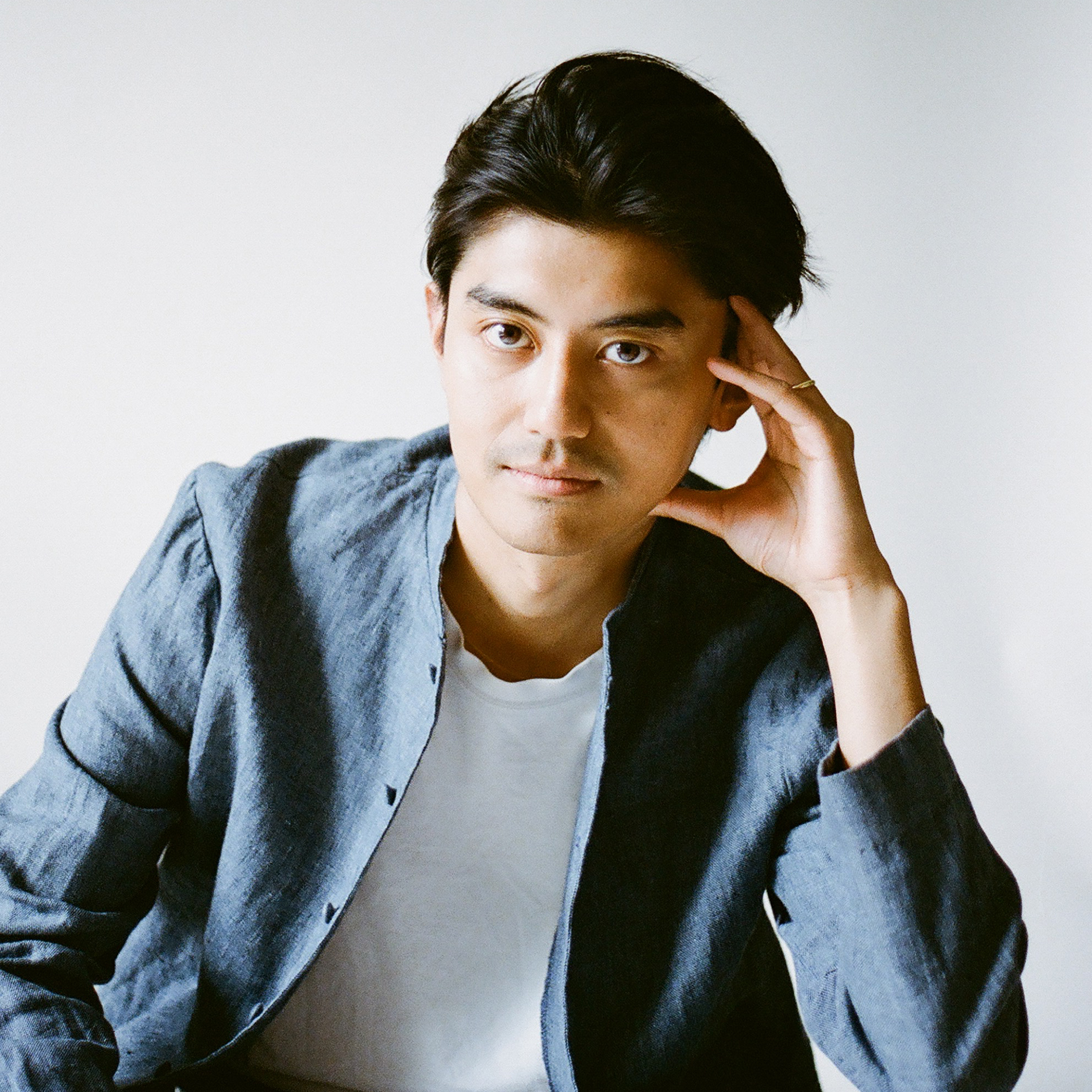

Philene Tan – Co-founder of Foundationals

The desire to take a mindful approach to consumerism has been more prominent in the eco-age than ever before. Co-founder Philene Tan of LA-based fashion brand Foundationals and her team are working tirelessly in coming out with ensembles that are not only eco-consciously made, but also affordable and fun to wear. As a young visionary with a passion in business, fashion and arts, the KL-born creative leader is spearheading the brand into a bigger scene.

Sustainability and practicality are at the forefront of your brand. What is the biggest challenge you and your team have faced so far?

One of our ongoing challenges is sourcing high quality sustainable materials for our pieces. There are many things we consider when choosing materials for a garment as a sustainability focused brand – where the raw material was grown and sourced, milled, the kinds of dyes used, washability, durability, its recyclability and biodegradability, etc. This is always the longest process in our R&D stage of product development.

Foundationals is transparent with the whole in-the-making process. Why do you think that is important for consumers today?

Large fast-fashion driven corporations have done a very thorough job over the past few decades in hiding or failing to disclose their involvement in human labour issues as well as their impacts of overconsumption and waste on the environment. The clothing industry is still one of the most polluting industries – and my thought is that it is our duty as next-generation brands to do our best to find genuine ways to be carbon positive and responsibility driven businesses. Fashion – or any industry that produces anything isn’t inherently “sustainable”, but it is 2021 and I think if you’re going to be producing any kind of output into the world, it’s got to be responsibly made. On the topic of transparency, we believe that if we share with customers about what goes on behind the scenes – to see the faces and hands that make their clothes – it’ll help them understand the amount of resources that go into making a simple sweater or T-shirt from start to finish. I think if more companies did this, we as consumers would begin to treasure our clothes more as opposed to treating them as mere disposables.

How has Foundationals as a brand evolved over this pandemic?

We have doubled down on our product range and have been focused on creating garments that are both chic and comfortable to wear on a variety of occasions. Post pandemic I think we will see a continued emphasis on comfort. I also think that customers will be more wary of the brands that they spend money on – and will prioritise brands that are authentic with their audience and that share the same values as them.

Two heads are better than one. That being said, how do you and your fellow co-founder Tim Tembrink find a common ground on everything that Foundationals does?

The great thing about working together is that there is a very clear distinction about who oversees what in our company. While I spearhead most of the creative aspects of our company, Tim is solely involved with the operational parts of Foundationals. We both trust each other’s work and collaborate openly a lot on decision making whether it be on a new product, new factory partnerships or new marketing ideas.

What would be your advice to those who want to start a successful sustainable fashion brand?

I think the most important thing is to make sure you are solving some kind of a gap in the market. Secondly, make sure that you work on establishing a supply chain – find the right factories that you work well with and that will help you with small production runs. Thirdly, never give up! If something doesn’t work, be open to deviating and trying something new quickly.

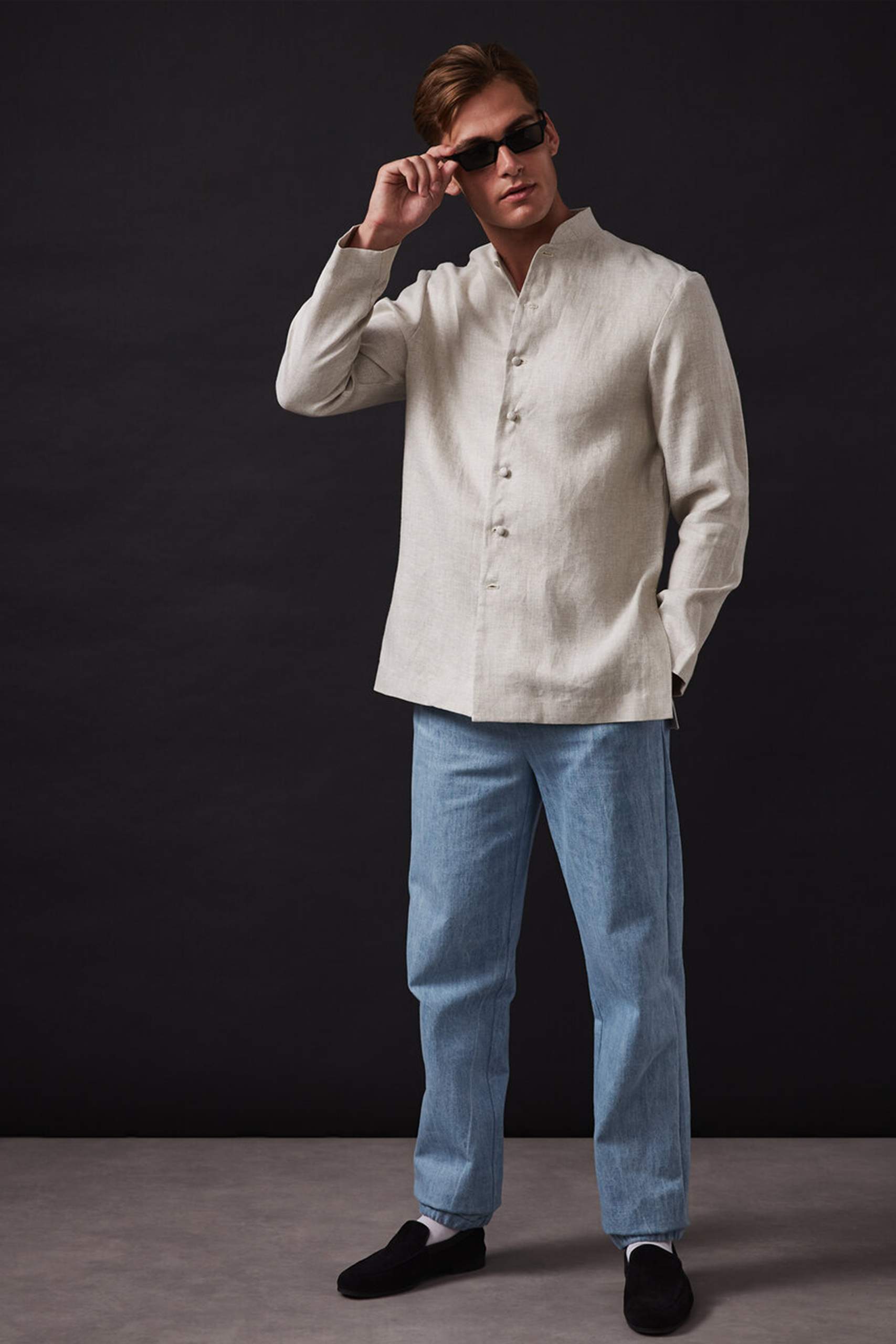

Mark Francis – Founder of Heron’s Ghyll

It’s no mean feat to translate a lifetime of experiences into a fashion brand – and that’s precisely what Mark Francis has done. From climbing up the corporate ladder to investment banking, working as a web developer to becoming a CEO of a fashion tech startup, Malaysian-raised multi-hyphenate Mark Francis is writing his latest chapter as a founder and designer of his own fashion label, Heron’s Ghyll. Recently launched in London, Francis is reconstructing the idea of conventional suiting, turning it into what’s called cosmopolitan tailoring, which essentially means made-to-measure garments that convey the same seriousness and refinement as a traditional suit without the corporate or gentlemanly connotations.

If you had to describe Heron’s Ghyll in five words, what would they be?

Cosmopolitan tailoring, made in London

What would you say is the gap that you are filling with Heron’s Ghyll?

Tailoring that doesn’t look like corporate attire and that’s comfortable enough for everyday wear. Culturally ambiguous attire that’s done tastefully, in luxurious fabrics, on a small scale, by skilled artisans creating in the English tailoring tradition.

Is that similar to your personal style?

I have many personal styles, and this caters to the times I want to signal that I’m same but different; like: “I’m well-versed in the art of European formalwear but also have these differences that I don’t feel the need to efface, that I embrace, and that make me interesting.” I’m proud of the part of my identity that was formed while growing up in Malaysia and don’t want to lose it while embracing my new life in London.

What was it like for you and your team to launch Heron’s Ghyll, considering we are still in a pandemic?

Stressful, but launching any new venture is stressful so I’m not sure how much of that was COVID-19 related. The thing I try to keep in the back of my mind is that Heron’s Ghyll is my 50-year plan so there’s no real hurry and no need to stress. I love what I do and I’m relishing every moment of the journey.

The pandemic has hit the fashion industry hard in so many ways. How has Heron’s Ghyll adapted to the impacts?

Heron’s Ghyll was launched at the start of the pandemic so working from home and having a digital workflow are second nature to us. But as restrictions have eased in London, we’ve been making the most of physical appointments and building our supplier relationships in-person. Fashion is such a tactile and relationship-driven business that there’s just no substitute for walking into Soho to feel fabrics or to get buttons covered.

What prompted you to start Heron’s Ghyll?

I always knew I would start a fashion brand, but I worked in everything from investment banking to web development to avoid doing the thing I wanted to do the most because I was scared. And then COVID-19 happened, and my options dwindled, and it seemed like an opportune moment to take the plunge so here I am.

Heron’s Ghyll is named after a small hamlet in the Sussex countryside. The name was chosen because, as someone who feels culturally dislocated, I wanted to ground the brand in a sense of place, to give it the roots I never had. And what better place than the fabled English countryside, where every story begins with “Once upon a time…”

This story first appeared in the September 2021 issue of Men’s Folio Malaysia.