When it was announced that musician and celebrity entrepreneur Pharrell Williams would lead operations for menswear at Louis Vuitton as the French Maison’s latest creative director, the reactions were divided. It had drawn massive criticism by the time it escalated on social media, and debates amongst disappointed and excited fashion adversaries were heated — to say the least. The exchanges were divided into two factions: one citing the announcement as troubling news to grasp, seeing that Williams might be “unqualified”, while the other saw the potential of Williams’ influence on Louis Vuitton. Between the noise, however, both sides agree on one thing — that the announcement was inevitable.

Williams’ appointment puts the term “creative director” in a unique position. During the weeks leading up to it, the rumours surrounding the French Maison’s replacement for the late-Virgil Abloh placed their faith in rising British designers Martine Rose and Grace Wales Bonner as the most suitable candidates. It made sense. If Louis Vuitton considered replicating Abloh’s previous culturally-led success, Rose and Bonner — black designers with an “underground” design pedigree — were their most obvious choices. What can Williams — known for radio-friendly pop hits “Happy” and “Get Lucky”, much less sewing shirts or crafting leather bags — bring to the table that neither designer might be able to? The answer is pretty simple. It provides a sense of culture, which is essential, especially when it can be instant, digestible — and just like Williams’ hit songs — be far-reaching and memorable.

Louis Vuitton has straddled the last few seasons without a menswear creative director, which has been made possible by expanding the narratives laid out by the late-Virgil Abloh’s tenure. Newly-appointed creative director Pharrell Williams is slated to present his debut collection during the Spring/Summer ’24 season.

Louis Vuitton has straddled the last few seasons without a menswear creative director, which has been made possible by expanding the narratives laid out by the late-Virgil Abloh’s tenure. Newly-appointed creative director Pharrell Williams is slated to present his debut collection during the Spring/Summer ’24 season.

So what does that make of a creative director’s role today? The pressing concerns towards Louis Vuitton’s idiosyncratic move are not isolated manifestations, largely as they arrive at a pivotal juncture in the trajectory of contemporary fashion. Two weeks before Williams’ announcement, Gucci revealed that Italian designer Sabato De Sarno would replace ex-creative director Alessandro Michele, who departed the House abruptly after a seven year stint. Rumours surrounding Michele’s replacement never expected Sarno. With a name relatively unknown within fashion’s inner circle, the appointment has been viewed as the most traditionalist one by a major fashion House in years.

It comes in tandem with Matthieu Blazy’s ascension at Bottega Veneta after taking over the role of creative director from ex-creative Daniel Lee while he was the brand’s lead designer. Despite months of speculation following Lee’s move to Burberry, Blazy’s appointment put fashion’s rotation of hires to a complete stop — whereby each time a house is looking for a new creative director, the search stops at a name already in charge of a successful House. The story is the same with Maximilian Davis’ hire at Ferragamo, who arrived at the House less than half a decade after finishing his education at the influential Central Saint Martins in London and only had his eponymous label as the best portfolio under his name.

While it sounds like tropes witnessed umpteen times, Davis, Blazy and Sarno’s assignments are part of a broader shift within the fashion sphere. Case in point — while the career trajectory for a creative director has always been streamlined, it might not be the case anymore. For decades, fashion Houses have leaned on designers to lead, revamp and proliferate their Maisons’ offerings — think Tom Ford at Gucci, Marc Jacobs at Louis Vuitton and most notably, Demna at Balenciaga. Indeed, the textbook reinvention does follow a synchronised pattern that most fashion Houses have adopted as repertoire, which began as soon as Tom Ford’s pivotal role in Gucci’s transformation during the 1990s — that received widespread acknowledgement.

While it sounds like tropes witnessed umpteen times, Davis, Blazy and Sarno’s assignments are part of a broader shift within the fashion sphere. Case in point — while the career trajectory for a creative director has always been streamlined, it might not be the case anymore. For decades, fashion Houses have leaned on designers to lead, revamp and proliferate their Maisons’ offerings — think Tom Ford at Gucci, Marc Jacobs at Louis Vuitton and most notably, Demna at Balenciaga. Indeed, the textbook reinvention does follow a synchronised pattern that most fashion Houses have adopted as repertoire, which began as soon as Tom Ford’s pivotal role in Gucci’s transformation during the 1990s — that received widespread acknowledgement.

Since then, the pressure to emulate the sensation Ford sparked was on. It manifested in hiring then-unknown designers with just the right amount of finesse to generate a cult following that can propel a House into contemporary propriety and at the same time, create celebrities of their designers, which were heavily influenced by superstar creatives such as Gianni Versace and Alexander McQueen.

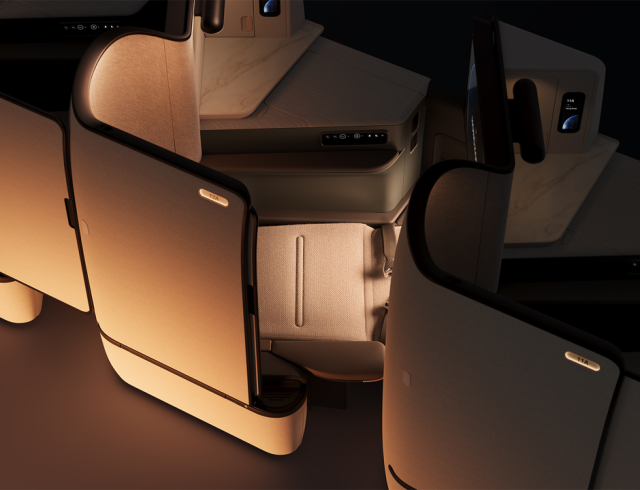

Bottega Veneta returns back to “soft power” with creative director Matthieu Blazy’s vision for the House after the abrupt departure of Daniel Lee — who is currently Burberry’s newly-appointed chief creative officer. Blazy is expected to fulfil his tenure for many more seasons to come.

Bottega Veneta returns back to “soft power” with creative director Matthieu Blazy’s vision for the House after the abrupt departure of Daniel Lee — who is currently Burberry’s newly-appointed chief creative officer. Blazy is expected to fulfil his tenure for many more seasons to come.

We eventually received epics eras in fashion where a House’s storied legacy were defined by a single designer, such as Hedi Slimane’s Saint Laurent, Olivier Rousteing at Balmain and the most noteworthy of all, John Galliano at Dior. Who would reject the pleasures of a fashion monarch? Not the consumers of today, it seems.

In the last three years, when have we encountered the resurgence of a celebrity designer hire? Davis, Blazy, and Sarno suggest that the need to replicate such sensations has waded out from fashion’s priorities. Take their commonality as a heralding point: talented designers with reserved personas, each with a unique point of view to offer and most importantly, at Houses that emphasise a need for quality and craftsmanship across all product ranges. The need for creative hires to forge a unique path and identity in an oversaturated market of vapid consumerism becomes crystal clear, especially since “mass appeal” has been dwindled by the rapid rise of individualism honed by Gen-Zs. For these Houses, the role of a creative director is now more than being a mere spokesperson.

While our current attraction to the celebrity designer of yesteryear still exists, it is also possible their influence has undeniably shrunk. On a wider perspective, the current stench of vanity in fashion now emanates as pungent — no one likes it when the designer’s name is larger than the House they are meant to steer. Despite our revived love affair for all things nostalgic, the romanticisation of its effect has lost any sense of palpable yearning for fashion’s newest and youngest audience. “Mass appeal” or not, the gritty authenticity and seeming simplicity found in the candidness of fashion’s newest auteurs is the preferred focal point now because they will never become more prominent than the House they are meant to represent. Perhaps, this is exactly why legacy Houses such as Gucci, Ferragamo, and Bottega Veneta reasoned with self-effacing personalities instead.

While our current attraction to the celebrity designer of yesteryear still exists, it is also possible their influence has undeniably shrunk. On a wider perspective, the current stench of vanity in fashion now emanates as pungent — no one likes it when the designer’s name is larger than the House they are meant to steer. Despite our revived love affair for all things nostalgic, the romanticisation of its effect has lost any sense of palpable yearning for fashion’s newest and youngest audience. “Mass appeal” or not, the gritty authenticity and seeming simplicity found in the candidness of fashion’s newest auteurs is the preferred focal point now because they will never become more prominent than the House they are meant to represent. Perhaps, this is exactly why legacy Houses such as Gucci, Ferragamo, and Bottega Veneta reasoned with self-effacing personalities instead.

However, that is not to say that superstar creatives have lost their appeal completely. For instance, Hedi Slimane’s hire at Celine after Phoebe Philo’s refinement of the house met the same criticism Louis Vuitton faced in February after Williams’ announcement. Regardless, consumers seemingly favoured the change as Celine’s 2021 export sales were worth €564.5 million as recorded by the LVMH conglomerate (Celine’s parent company), signalling an 81% increase since Slimane’s appointment in 2018. Slimane has amassed a cult following since his days as creative director of Dior Homme during its inception, and it seemed like a strategic move to reproduce his influence on a reserved House such as Celine. Yet, there is also Riccardo Tisci’s brief stint at Burberry, which was met with disappointing growth — revenue at comparable exchange rates dipped by 1 per cent year-on-year to £2.72 billion while pre-tax profit increased by about 7 per cent over the comparable period to £441 million, slightly under analyst expectations.

Where does that leave Louis Vuitton’s celebrity hire, then? It seems the subject of creative directors today is a complicated topic of discussion, whether the specifics of that role have changed at all. While it remains a fact that the role of a creative director has also evolved from mere product designer to stewards of pop-culture dissemination, there is also a need to consider the important aspect of celebrity endorsements.

Where does that leave Louis Vuitton’s celebrity hire, then? It seems the subject of creative directors today is a complicated topic of discussion, whether the specifics of that role have changed at all. While it remains a fact that the role of a creative director has also evolved from mere product designer to stewards of pop-culture dissemination, there is also a need to consider the important aspect of celebrity endorsements.

Some Houses might have abstained from celebrity designer hires as they have considered their brand ambassadors as the true personification of their Maisons. With RM of BTS’ announcement as Bottega Veneta’s official brand ambassador, the need for a celebrity designer might be redundant coming from a House that has never once announced any celebrity endorsements. Williams’ appointment at Louis Vuitton could fulfil two needs with one deed — a creative director who can also lead as its best ambassador. It will be interesting to see how Williams’ tenure will pan out, but one thing is certain; there will be a snowball effect on Louis Vuitton’s profits. And if so, expect other brands to follow suit as well.