Mechanical timepieces have long stood as enduring symbols of love as compared to quartz watches — here’s why.

The universe of watches is a wide and diverse one — there exists a flavour for every taste. As such, there are numerous dichotomies within said universe — digital and analog, precious metal and steel cases, and the list goes on. Arguably, the biggest binary is in terms of movement — in particular, the (possibly eternal) divide between quartz and mechanical movements. Considering that the realm of mechanical watches — which began around 1810 — was almost blitzed into oblivion by the popularity of quartz watches back in the 1970s to early 1980s, today’s perception of mechanical watches compared to their quartz siblings since then has been nothing short of a remarkable reversal of roles. Given that premise, the question must be asked: what changed in the fifty years or so since the Quartz Crisis?

The Quartz Crisis — A Brief History

The answer to that lies in a balance between human psychology and horology — specifically, inherent competitiveness, fascination with technology, and love for “hype”. To put it briefly, quartz watches’ widespread popularity at the time arose out of fierce competition amongst watchmakers to manufacture the first quartz wristwatch — then considered a huge technological leap forward in the realm of horology. Ironically, however, the same psyche that fuelled the rise of quartz watches led to the loss of its appeal.

Swiss mechanical watchmakers’ hesitancy in embracing the new quartz technology meant that Japanese and American watchmakers began to dominate the market. In no time, it was flooded by cheap, mass-produced, more accurate quartz watches, making it more cost-effective to just get a new watch when the electronics and circuitry within the movement inevitably wore out, rather than send it for repairs. Consequently, this forever altered the perception of quartz timepieces — instead of instruments that could reliably transcend lifetimes, they became cheap and disposable accessories.

Swiss mechanical watchmakers’ hesitancy in embracing the new quartz technology meant that Japanese and American watchmakers began to dominate the market. In no time, it was flooded by cheap, mass-produced, more accurate quartz watches, making it more cost-effective to just get a new watch when the electronics and circuitry within the movement inevitably wore out, rather than send it for repairs. Consequently, this forever altered the perception of quartz timepieces — instead of instruments that could reliably transcend lifetimes, they became cheap and disposable accessories.

The Swiss answer to the Quartz Crisis further reinforced this change in perception. The two biggest watch groups in Switzerland merged to form the Swatch Group, intending to revive the Swiss watch industry through channeling pop-culture and fashion into horology. The result was cheap, mass produced Swiss quartz movements permanently enclosed in brightly-coloured plastic cases, deriving design inspiration directly from the pop-culture realms of fashion and art. Their plan worked — two and a half million of such examples sold in just two years, but this meant the “cheap and disposable quartz” tag well and truly stuck.

The Swiss answer to the Quartz Crisis further reinforced this change in perception. The two biggest watch groups in Switzerland merged to form the Swatch Group, intending to revive the Swiss watch industry through channeling pop-culture and fashion into horology. The result was cheap, mass produced Swiss quartz movements permanently enclosed in brightly-coloured plastic cases, deriving design inspiration directly from the pop-culture realms of fashion and art. Their plan worked — two and a half million of such examples sold in just two years, but this meant the “cheap and disposable quartz” tag well and truly stuck.

Furthermore, Swiss mechanical watchmakers were also beginning to find their feet again by that point. In an incredible display of foresight, Zenith senior engineer Charles Vermot defied the order to throw out the machinery and equipment needed to make the legendary El Primero movement. He elected to hide them instead — together with the detailed written record of the movement’s manufacturing process — in a storage attic in the Le Locle manufacture’s factory. Vermot’s decision was rewarded when Rolex came knocking in 1982, in search of a self-winding chronograph movement for the Daytona. When it was introduced six years later, the El Primero-powered Daytona heralded the renaissance of mechanical timepieces, and set the stage for the golden age to come, spearheaded by the iconic, Gérald Genta-designed Audemars Piguet Royal Oak and Patek Philippe Nautilus.

Furthermore, Swiss mechanical watchmakers were also beginning to find their feet again by that point. In an incredible display of foresight, Zenith senior engineer Charles Vermot defied the order to throw out the machinery and equipment needed to make the legendary El Primero movement. He elected to hide them instead — together with the detailed written record of the movement’s manufacturing process — in a storage attic in the Le Locle manufacture’s factory. Vermot’s decision was rewarded when Rolex came knocking in 1982, in search of a self-winding chronograph movement for the Daytona. When it was introduced six years later, the El Primero-powered Daytona heralded the renaissance of mechanical timepieces, and set the stage for the golden age to come, spearheaded by the iconic, Gérald Genta-designed Audemars Piguet Royal Oak and Patek Philippe Nautilus.

The Modern Outlook

Today, that “cheap and disposable quartz” perception is still very much present. Grand Seiko’s 9R Spring Drive movement — that combines the power source of a traditional mechanical movement (the hairspring) with the quartz crystal regulator from a quartz watch — is a truly innovative work of horological engineering, but some still scoff at it because of the quartz components within the movement.

The criticisms of Swatch’s recent collaborations with established mechanical watchmakers Omega and Blancpain are also telling. Most of the brickbats directed at the former are aimed at the ‘MoonSwatch’s’ quartz movement, and how it is irremovably sealed in a bioceramic case — detractors claim it cheapens the legacy of Omega’s iconic space-sailing timepiece.

The latter is a more unique case study — true to Blancpain’s ethos of never manufacturing a quartz watch, the movement at the heart of the ‘Scuba Fifty Fathoms‘ is the mechanical SISTEM51. One would imagine that the critics would therefore have eased up, but — interestingly — that was not the case. Given the movement is also permanently sealed into a bioceramic case and therefore cannot be removed for repair or servicing (as you would expect on a regular mechanical watch), the timepiece was slapped with the same “cheap and irreparable” tag as the ‘MoonSwatch’. Swatch — once again — found themselves facing similar accusations of cheapening the legacy of Blancpain’s definitive diver for the sake of “hype”.

The latter is a more unique case study — true to Blancpain’s ethos of never manufacturing a quartz watch, the movement at the heart of the ‘Scuba Fifty Fathoms‘ is the mechanical SISTEM51. One would imagine that the critics would therefore have eased up, but — interestingly — that was not the case. Given the movement is also permanently sealed into a bioceramic case and therefore cannot be removed for repair or servicing (as you would expect on a regular mechanical watch), the timepiece was slapped with the same “cheap and irreparable” tag as the ‘MoonSwatch’. Swatch — once again — found themselves facing similar accusations of cheapening the legacy of Blancpain’s definitive diver for the sake of “hype”.

The Romanticism of Symbolism

While it is undeniable that these public perceptions are partially shaped and fostered through decades of marketing and the effect of a herd mentality, it must be acknowledged in equal measure that mechanical watches are just simply different — they possess a romantic, nearly-human quality. As mentioned earlier — with the right amount of TLC, it is almost an expectation that mechanical watches outlive the owners they become extensions of.

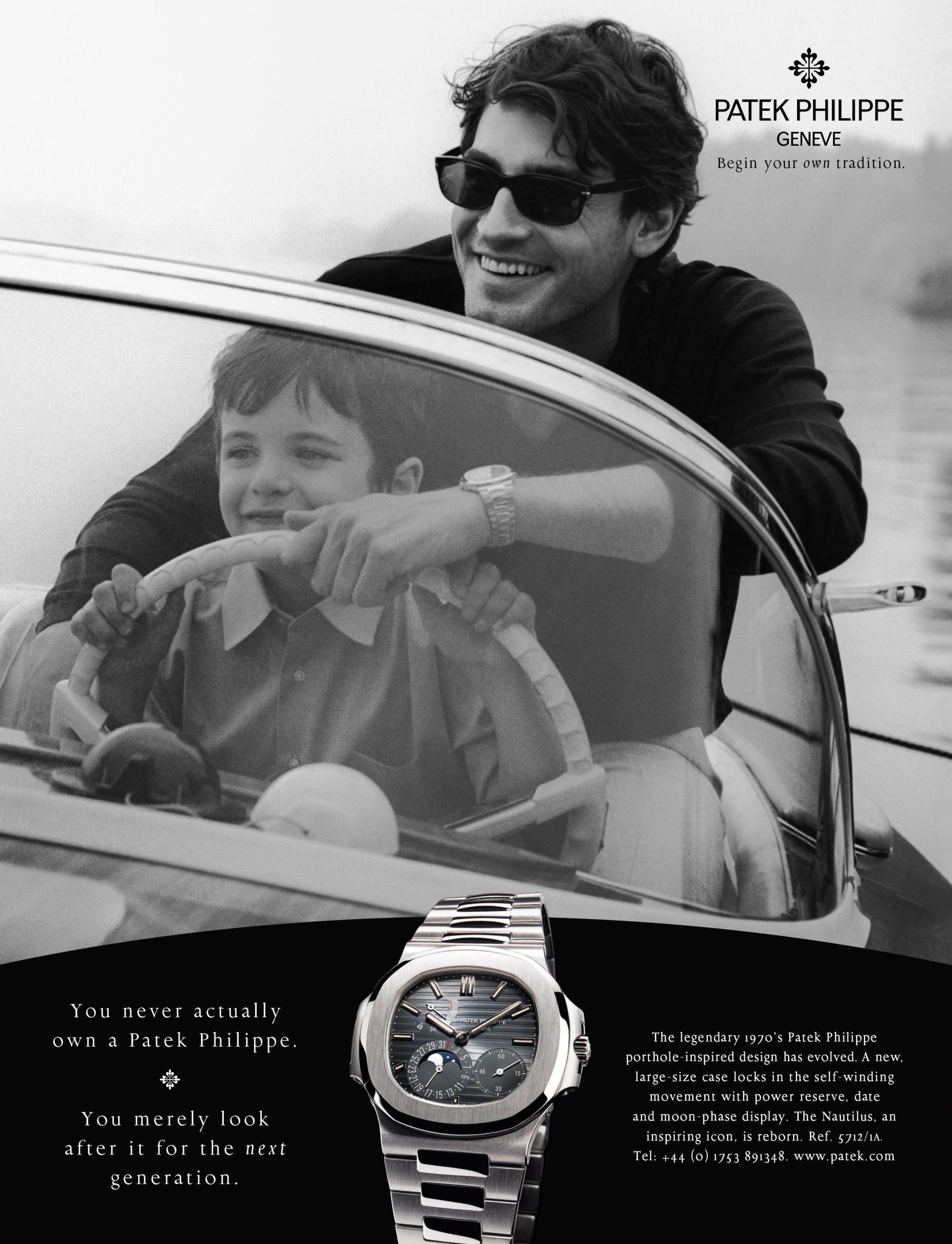

Mechanical watchmakers recognise that quality too — Patek Philippe romanticised this sentiment in its most iconic and enduring campaign, proclaiming that “You never actually own a Patek Philippe. You merely look after it for the next generation”. Since its appearance in 1996, that campaign slogan now speaks more for mechanical watches as a whole rather than just Patek Philippe. Hence, compared to the relatively shorter lifespan of quartz watches, mechanical watches — imbued with a romanticised, transcendental ability to transmit principles and values across generations — command a deeper sense of symbolism. Just as a particular dish, scent, or song has the ability to rekindle memories deeply buried, so too a mechanical timepiece possesses that same ability to transport the wearer “back in time”, serving as a tangible, ticking symbol of its previous wearer’s memory.

Mechanical watchmakers recognise that quality too — Patek Philippe romanticised this sentiment in its most iconic and enduring campaign, proclaiming that “You never actually own a Patek Philippe. You merely look after it for the next generation”. Since its appearance in 1996, that campaign slogan now speaks more for mechanical watches as a whole rather than just Patek Philippe. Hence, compared to the relatively shorter lifespan of quartz watches, mechanical watches — imbued with a romanticised, transcendental ability to transmit principles and values across generations — command a deeper sense of symbolism. Just as a particular dish, scent, or song has the ability to rekindle memories deeply buried, so too a mechanical timepiece possesses that same ability to transport the wearer “back in time”, serving as a tangible, ticking symbol of its previous wearer’s memory.

Staying on the topic of symbolism, mechanical watches also mirror humanity in its imperfect nature. Humankind has always expressed discomfort at perfection, mainly due to its unattainability — it’s why the uncanny valley theory exists. In a horological sense, mechanical watches cannot be compared to its quartz siblings in terms of maintaining accuracy, and need constant care in order to deliver on the promise of longevity. That horological imperfection is a reflection of our own human flaws — making mechanical watches fitting canvases upon which Man projects meaning.

The Gift of Time

It comes as no surprise then, that mechanical watches make meaningful gifts, with many high-profile examples acquiring mythical status within the realm of pop-culture. One of the earliest recorded examples is the Breguet Grande Complication ‘No.160’ pocket watch, commissioned in 1783 by a secret admirer as a gift for Marie Antoinette, although it never reached her hands. The timepiece’s history reads like the plot of a heist movie — it was stolen in 1983 by thief Na’aman Diller, and then unexpectedly returned to its home in the Museum of Islamic Art in Jerusalem by his wife, after his death in 2007.

John Lennon’s rare Tiffany-signed Patek Philippe ref. 2499 perpetual calendar chronograph — dominating horological headlines as recently as last September — shares a similarly turbulent history. A gift to the Beatles rocker from his wife Yoko Ono on his 40th birthday in 1980, he was murdered just two months later. In 2006, the watch was stolen by Ono’s private driver, then passed to a now-defunct auction house in 2009 and privately sold to an Italian dealer in 2014. Following his attempt to sell it to another auction house — Christie’s — that same year, they alerted Ono’s attorney — only then did she discover that the watch was no longer with her.

John Lennon’s rare Tiffany-signed Patek Philippe ref. 2499 perpetual calendar chronograph — dominating horological headlines as recently as last September — shares a similarly turbulent history. A gift to the Beatles rocker from his wife Yoko Ono on his 40th birthday in 1980, he was murdered just two months later. In 2006, the watch was stolen by Ono’s private driver, then passed to a now-defunct auction house in 2009 and privately sold to an Italian dealer in 2014. Following his attempt to sell it to another auction house — Christie’s — that same year, they alerted Ono’s attorney — only then did she discover that the watch was no longer with her.

A legal tussle between Ono and the Italian dealer ensued, with a Geneva court eventually ruling that Ono was the watch’s rightful owner nearly a decade later in 2023. If anything, the stress Ono endured, and the determination she displayed to retrieve the watch across nearly a decade, defines the watch as more than just a time-telling tool. Given the history of the watch, it is arguably a hauntingly-fitting embodiment of the rekindled romance and passion she shared with Lennon, in that brief time before he was tragically assassinated.

A legal tussle between Ono and the Italian dealer ensued, with a Geneva court eventually ruling that Ono was the watch’s rightful owner nearly a decade later in 2023. If anything, the stress Ono endured, and the determination she displayed to retrieve the watch across nearly a decade, defines the watch as more than just a time-telling tool. Given the history of the watch, it is arguably a hauntingly-fitting embodiment of the rekindled romance and passion she shared with Lennon, in that brief time before he was tragically assassinated.

That these two timepieces are widely considered the most important and valuable on the planet today speaks for the magic that mechanical timepieces possess as enduring symbols of love and passion, and the timeless romance they help engender.

Other — albeit less controversial — examples include the gold Vacheron Constantin dress watch gifted to Marlon Brando by lover Zsa Zsa Gabor in 1954, and the similarly-hued Cartier Tank Française Meghan Markle received from Prince Harry in 2022. The latter is an especially intimate gift — if the rumours are true, the Tank Française’s previous owner was none other than Princess Diana herself, lending the timepiece an additional layer of sentimentality and historical significance.

All of this isn’t to say that quartz watches are inferior in any way to their mechanical siblings — ultimately, watches in general have been and will always be sentimental symbols of rose-tinted romance. That said, there is simply no substitute for a humanly-imperfect object with a ticking heart, that — with the requisite love and devotion — can live forever. Humans will always crave the latest innovative technology and chase the highs that “hype” delivers, but nothing will take away from the romance of something that — theoretically at least — endures for eternity.

All of this isn’t to say that quartz watches are inferior in any way to their mechanical siblings — ultimately, watches in general have been and will always be sentimental symbols of rose-tinted romance. That said, there is simply no substitute for a humanly-imperfect object with a ticking heart, that — with the requisite love and devotion — can live forever. Humans will always crave the latest innovative technology and chase the highs that “hype” delivers, but nothing will take away from the romance of something that — theoretically at least — endures for eternity.

In that regard, there is no greater ode to transcendental love than the mechanical timepiece.

Once you are done with this story, click here to catch up with our June/July 2024 issue.