After independent creative director Sybille de Saint Louvent’s AI-generated fashion campaigns blew up online, the creative industry found itself in the middle of a debate: is AI killing originality, or does it push the boundaries of creative potential? As algorithms start mimicking human instinct and machine-made art gets harder to distinguish from the real thing, the line between innovation and imitation is looking blurrier than ever.

Men’s Folio Malaysia talks to Chong Yan Chuah, a Kuala Lumpur-based artist, architect, and designer to break down what AI really means for the future of creativity. And whether it’s a revolution, a threat, or just another passing trend.

Your 2021 project, “FAC3D”, delved into the intersection between human identity and the virtual world. Could you share your experience using OpenAI back then and how you’ve seen that kind of technology developed since?

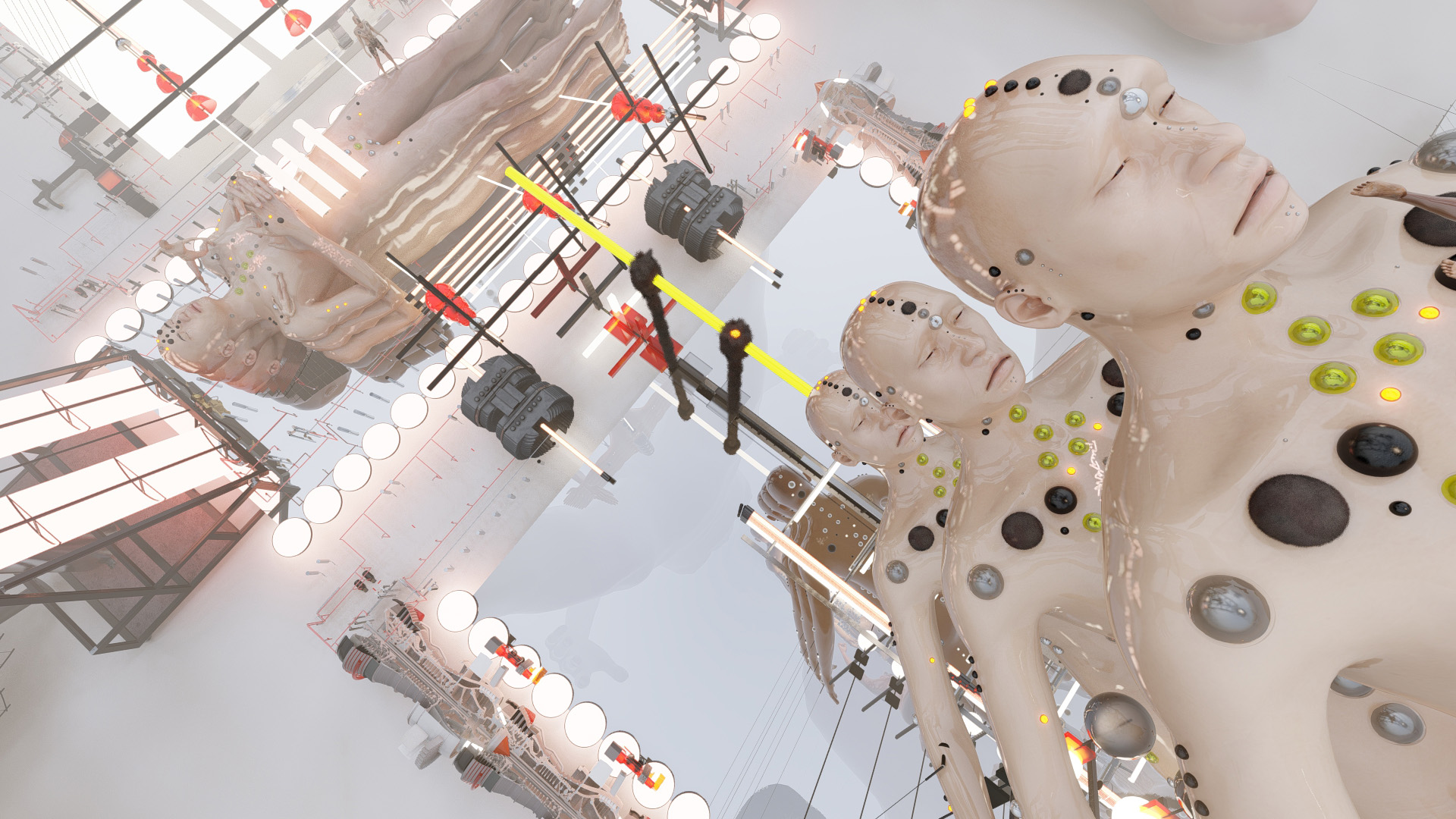

FAC3D was a pivotal project where I explored how virtual bodies and avatars mediate self-perception and agency. It was a playground where I dissected identity in the digital realm, exploring the ways avatars mediate self-perception and agency.

Back then, I experimented with OpenAI’s early models, using them to generate text-based narratives and datasets that became the conceptual basis for my work. The technology was promising but a little naive, its potential was apparent, but it was still learning how to see, to feel.

Now, AI creates hyper-detailed environments, spins intricate narratives, and even makes aesthetic choices that rival the human hand, raising questions about authorship and agency in creative fields.

I dream of stepping into the role of a virtual architect, digital shaman, and techno-pagan, crafting blueprints of the unseen and building speculative worlds where the sacred and the synthetic meet. AI has become an essential part of this journey, allowing me to push the scale, dimension, and data-driven aesthetics in ways that once felt impossible.

In Malaysia, we’re seeing brands experiment with AI to generate campaign visuals, predict trends, and even design clothing. Given our cultural and consumer landscape, do you think AI can truly capture the nuances of local fashion, or does it risk making everything look algorithmically ‘globalised’?

AI’s immense power to predict and shape fashion trends is intoxicating but its potential comes with the risk of homogenising aesthetics and flattening cultural specificity. Fashion, like any form of cultural expression, is deeply rooted in the rituals, histories, and lived experiences of a place.

So, while trend forecasting and future insight reports highlight how AI is reshaping fashion through predictive analytics and generative design, they also caution against the dangers of aesthetic uniformity driven by globalised datasets.

A key issue is algorithmic bias trained predominantly on datasets, AI tends to prioritise mainstream, Western-centric aesthetics while marginalising localised and indigenous design languages. If AI’s training data lacks representation of Southeast Asian textiles, patterns, and silhouettes, its outputs risk erasing or misinterpreting these cultural nuances.

Bias in machine learning not only shapes what the technology produces but also dictates what it fails to see, reinforcing existing hierarchies in global fashion rather than challenging them.

In my work, I draw from the mythologies of the Sino-Malay Archipelago, infusing digital landscapes with cryptic iconography and esoteric symbology to create spaces that feel ritualistic and otherworldly.

The challenge for AI in fashion is whether it can internalise these layers of meaning, rather than merely pattern-match from existing data. Much like how I use ChatGPT to articulate and refine my thoughts, AI can serve as a tool to enhance rather than replace human creativity.

However, without critical oversight and localised dataset training, it risks perpetuating a kind of algorithmic amnesia, where cultural specificity is flattened in favour of aesthetics dictated by the most represented data.

While AI-generated campaigns are visually impressive, critics argue that they lack the human touch—especially in fashion, where storytelling and cultural context play a major role. In your opinion, can AI ever replicate the emotional resonance of a well-crafted, human-led campaign?

AI can generate beauty, yes. AI can mimic emotion, sculpt drama, even compose poetry; but true resonance? That comes from something deeper. Something lived. Emotion isn’t just a visual construct, it’s layered with memory, longing, the intangible weight of existence.

That’s why, in my practice, I create speculative worlds as ritualistic spaces, where digital shamanism and techno-pagan aesthetics meet contemporary anxieties. AI can be my co-conspirator, my celestial handmaiden — whispering suggestions, tweaking the light, sharpening the lines.

But the invocation, the mythos, the weight of cultural memory, that remains mine to summon. It can simulate sentiment, but the soul of the work? That must be forged in human fire.

If so, how can creatives use AI without losing the human element?

The key is to position AI as an enabler rather than a replacement. I engage with this technology as a tool to manipulate scale, form, and narrative structures, yet the guiding vision remains inherently human. By integrating it into creative workflows as an instrument of augmentation rather than automation, artists can expand their practice without giving up authorship.

AI’s capacity to generate textures or forms provides raw material, but the final composition must still bear the artist’s intentionality. Just as I incorporate ancient cosmologies with digital architecture to construct speculative mythologies, AI should serve to elevate, not overwrite, human creativity, functioning not as an originator, but as a conduit for deeper artistic exploration.

AI-generated content depends on vast amounts of data, raising concerns about ownership, ethics, and privacy. Given this, what is the current state of Malaysian intellectual property laws regarding AI-generated works? And what are the risks of operating in a space with unclear or absent regulations?

Malaysia, like much of the world, is still catching up to AI. Our legal frameworks don’t quite know how to define this type of technology yet. Who owns what it creates? The programmer? The user? AI itself? It’s a legal limbo, and within that uncertainty comes risks—exploitation of artists, unregulated data scraping, and algorithmic bias that reinforces existing power structures.

My work critically engages with these tensions, placing AI within a broader mythology where the digital is not merely a tool but a metaphysical construct. We need frameworks that acknowledge its role in creativity while protecting human labour and cultural authorship.

With AI blurring the lines of visual originality, to what extent do you think the incorporation of AI is acceptable in the creative process of visual art and campaigns by creatives without diminishing the human element and authenticity? And how does this affect how audiences perceive their work?

The integration of AI into creative work is not inherently inauthentic, it depends on how it is used. In my practice, I work with it to extend the limits of my creative vision, not to replace my own intuition. My speculative worlds are imbued with the mythological weight of the Malay Archipelago, a map of alternative cosmologies where the sacred and synthetic converge.

If it is used with intention, trained on culturally relevant datasets, and employed as a collaborator rather than a creator, AI can deepen the layers of visual storytelling rather than dilute them. The audience’s perception will shift based on transparency. If they understand it as an instrument of expansion rather than automation, they will be more open to its role in contemporary art.

With AI becoming more embedded in industries, there’s rising concern about companies replacing human talent with AI-generated content to cut costs. What steps should the creative industry take to ensure AI remains a tool for innovation rather than a replacement for human artistry?

The industry must advocate for AI technology literacy, for ethical guidelines, for fair compensation models. AI should not be wielded as a cost-cutting scalpel but as a means of expanding creative horizons. Just as I use it to generate speculative terrains, digital architectures, and cryptic iconographies, AI should be a tool of augmentation, not automation.

In order to keep this technology in check, we must push for frameworks that ensure human oversight, emphasise co-creation, and position AI as an amplifier of artistic expression rather than an eraser of human labour.

AI is a fascinating companion, a tool presenting endless possibilities, but in the end, it is humans who must compose the song. If AI is to shape the future of creativity, how do we ensure its echoes do not drown out the voices of those who first taught it to sing?

Once you are done with this story, click here to catch up with our latest issue.