Pictured above: (On Amir Ahnaf) Coat, pants, all Prada

The journey from boy to man is anything but linear, and masculinity means different things to different people. For actors Amir Ahnaf, Aedy Ashraf, and Sky Iskandar, this complex theme is not just lived through their own boyhood, but revisited through their portrayals of Kahar, Beja, and Megat in the much-anticipated Projek Kahar: Order Breeds Chaos.

Set in the cloistered halls of Malaysia’s esteemed boarding schools, the movie probes the many facets of masculinity, part of which includes bullying. What goes on behind these institutions that are often synonymised with education and bright futures? And what lessons — or scars — do these boys take with them once they leave?

Men’s Folio Malaysia sits with the actors of Projek Kahar to pick their thoughts on what it means to grow up as a man today, and where bullying belongs in this topic.

Our father’s sons

Legacy is the central theme of Projek Kahar, a narrative that follows Kahar’s fractured relationship with his father and the intense pressure to live up to the image of his older brother, Beja. Sometimes, it is the educational institutions that plant the seed of fear or inadequacies in our minds. But home is where the problems can start too.

The phrase “kita anak ayah”, meaning “we are our father’s sons”, echoes throughout Projek Kahar. In Malay culture, the concept of anak lelaki (sons) carries a heavy duality: the pride of being a family’s torchbearer and the suffocating pressure to conform to ideals of strength and sacrifice. Fathers pass down lessons meant to prepare their sons for life’s battles, but those lessons — “boys never cry” or “man up” — can sometimes do more harm than good.

Aedy, who plays Beja, comments on the subject: “The idea of honouring your family is beautiful, but what happens when it crushes who you are? Projek Kahar is not just about individual struggles — it is about breaking generational cycles.”

And therein lies the genesis of going down the wrong path in masculinity. If the expectations at home already lead impressionable young men towards toxic behaviour or bullying, then entering institutions that promote said behaviour will only add fuel to the fire.

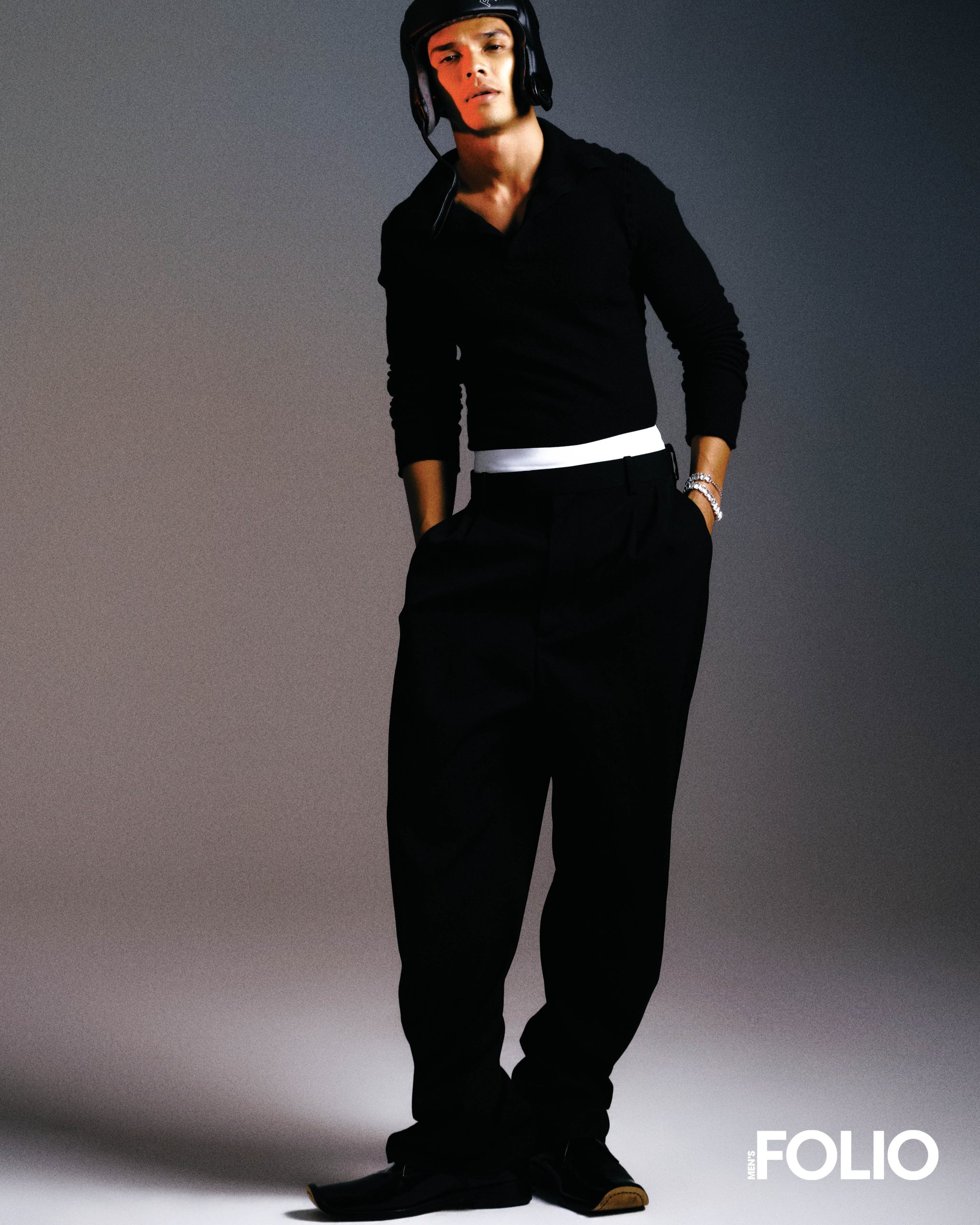

(On Aedy Ashraf) Sweater, pants, Bottega Veneta; Necklace (worn as a bracelet), Swarovski; Helmet, briefs, Stylist’s own

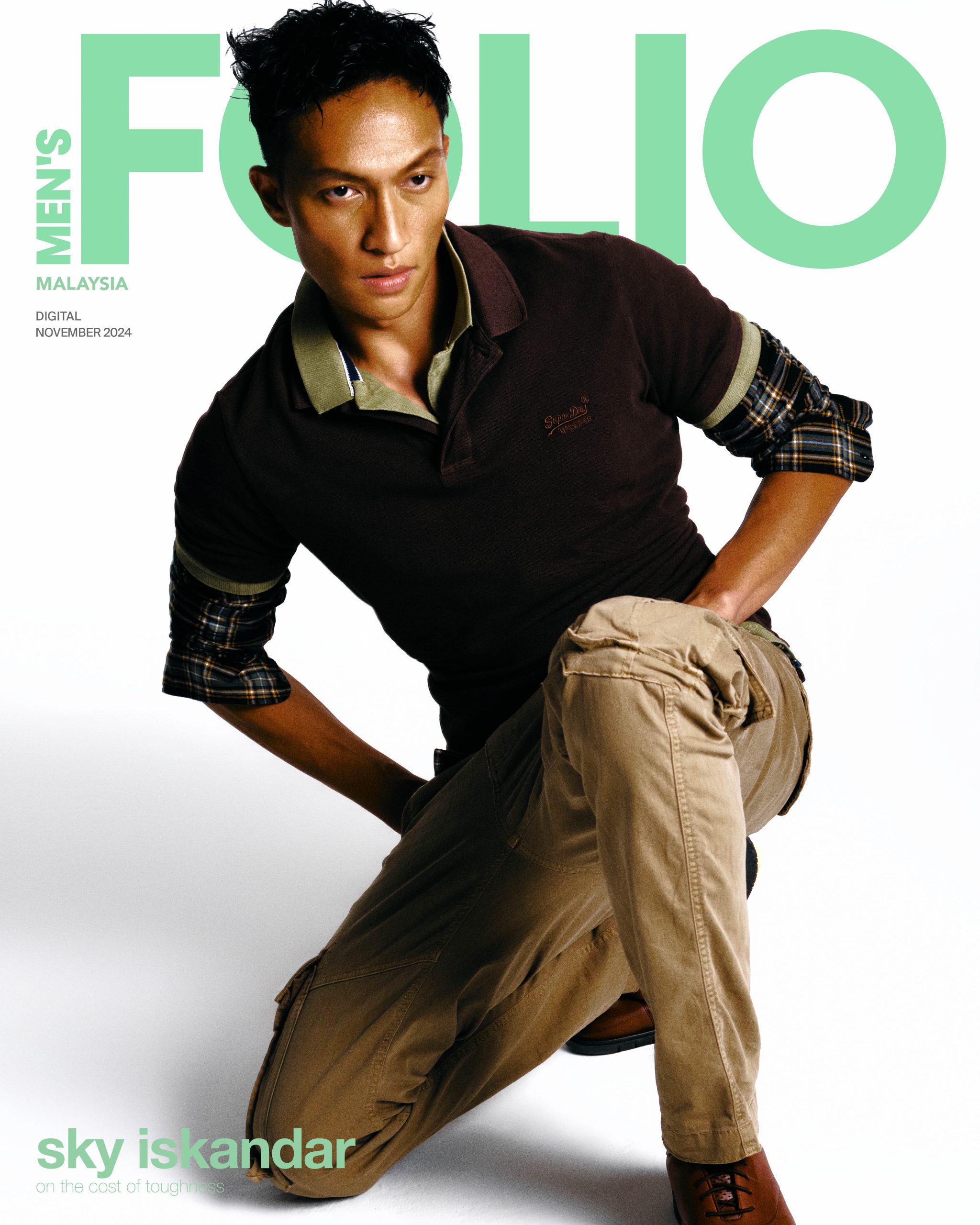

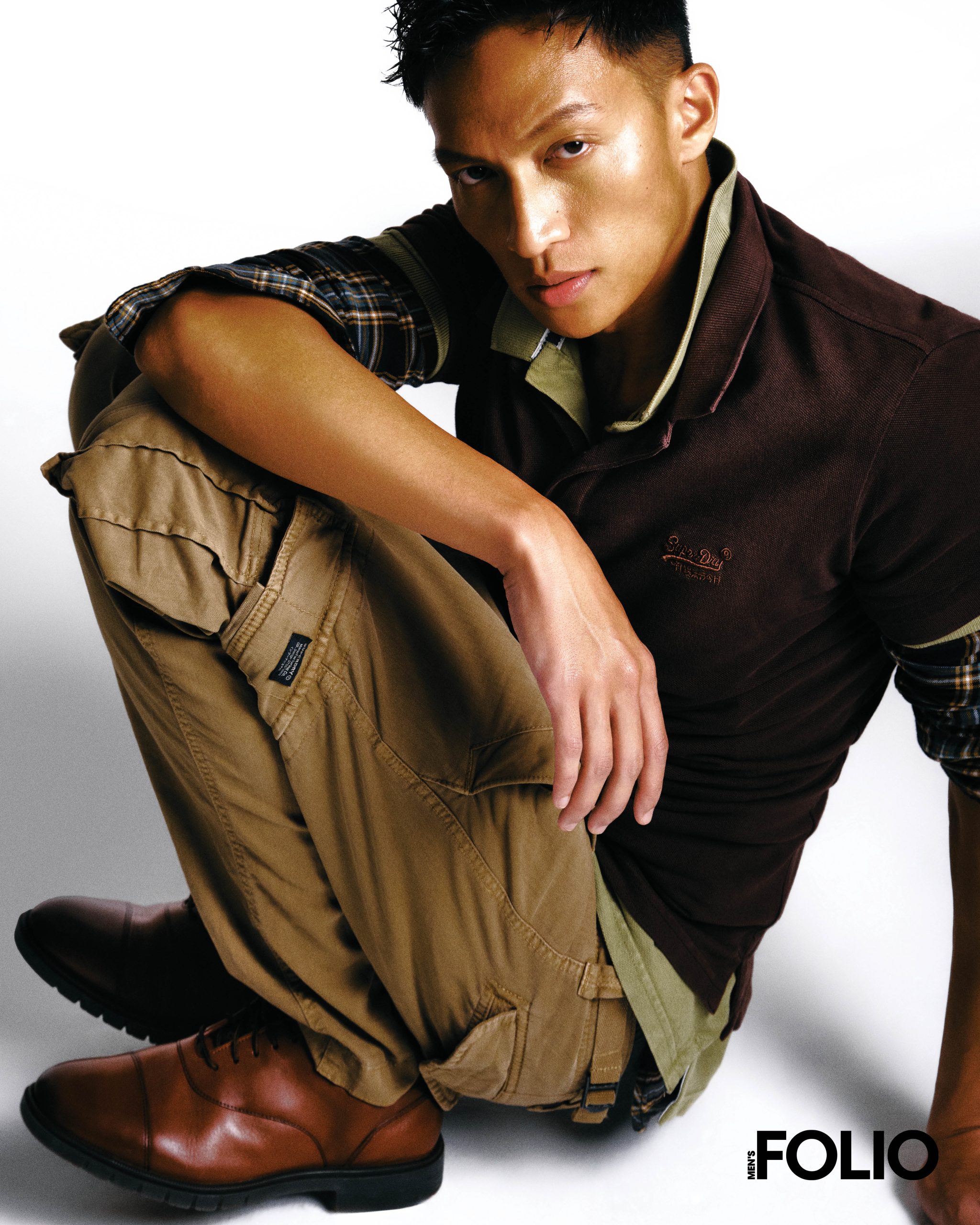

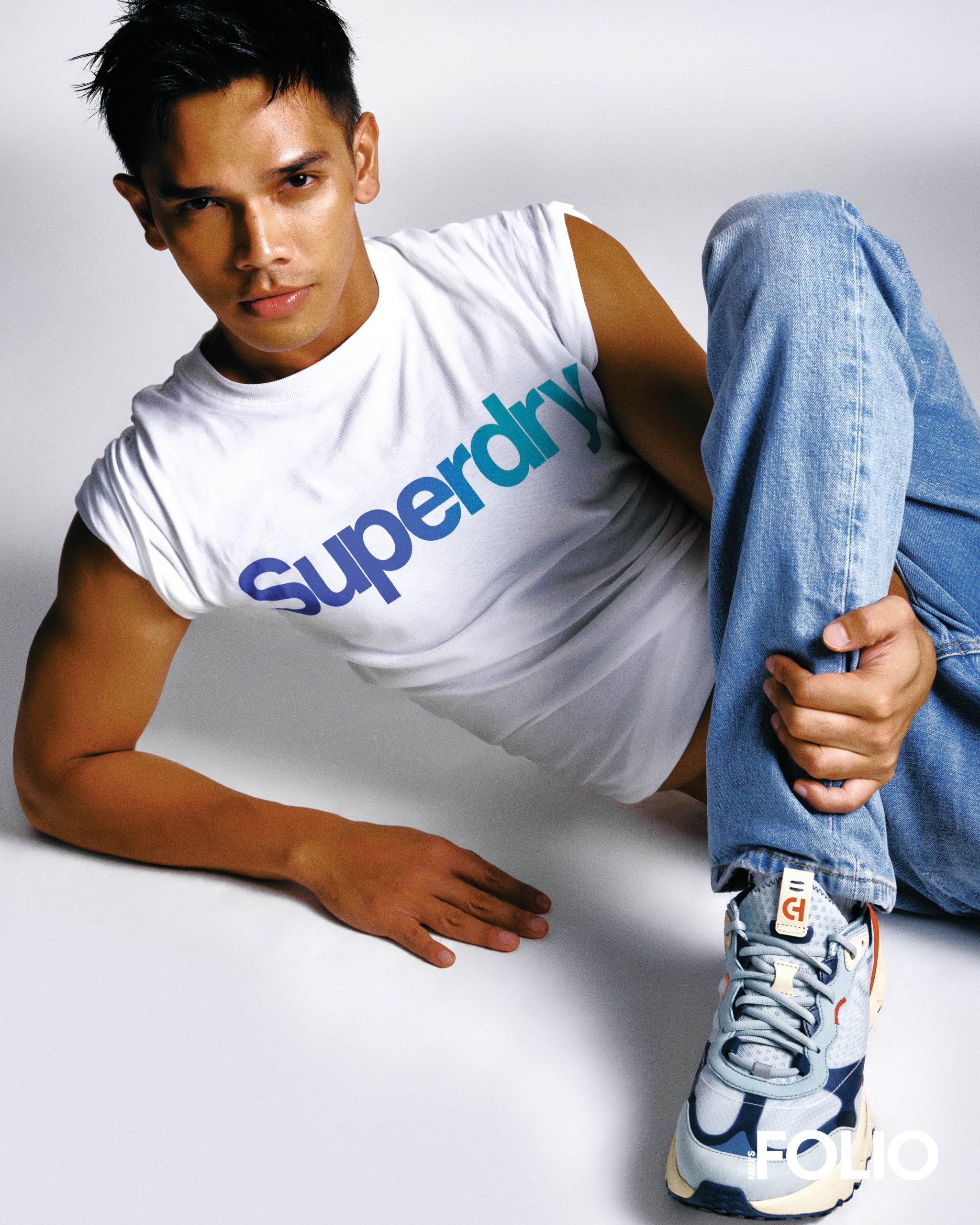

(On Sky Iskandar) Polo shirts, Shirt (worn as an inner), pants, Superdry; Shoes, Cole Haan

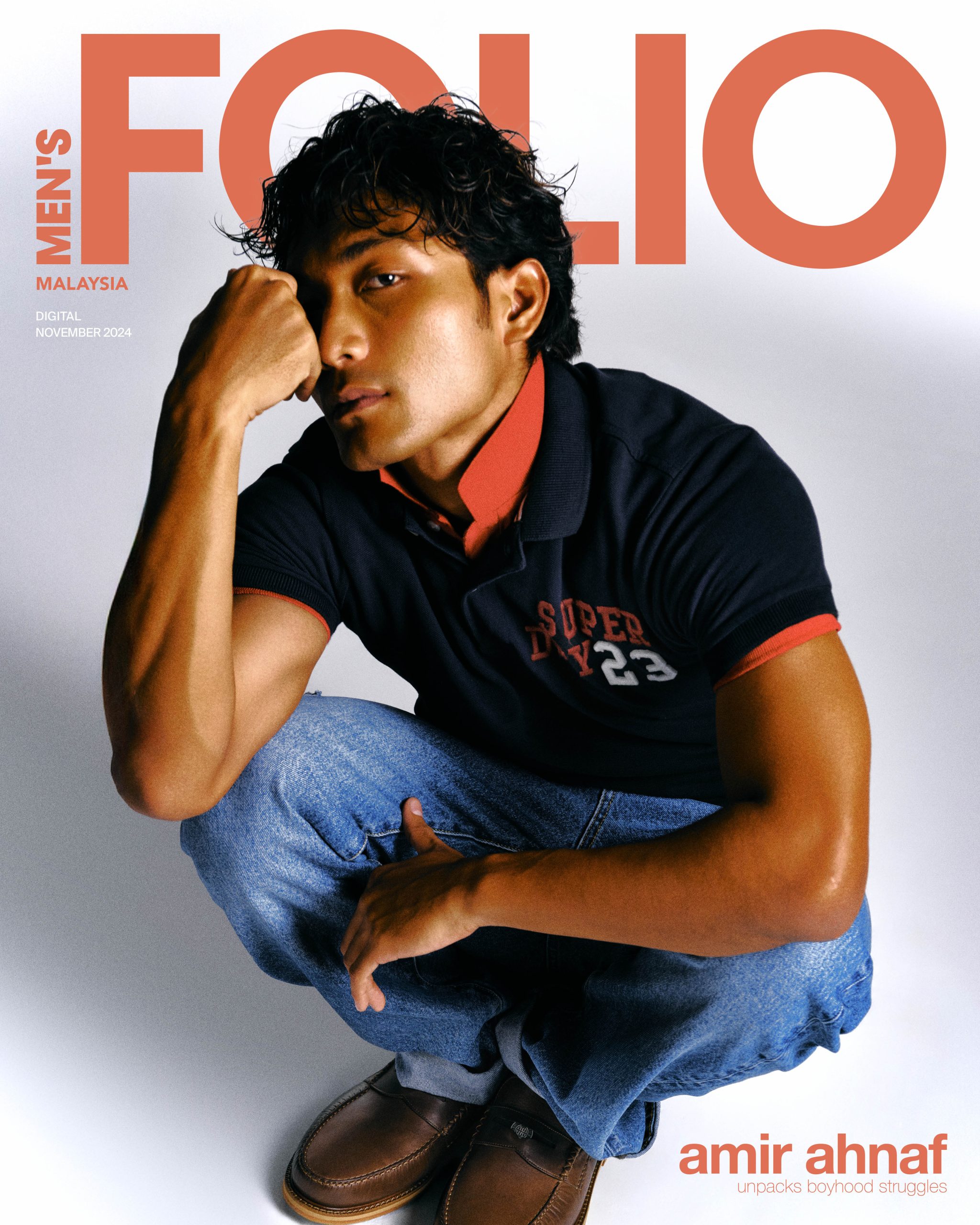

(On Amir Ahnaf) Polo shirts, jeans, Superdry; Shoes, Cole Haan

Masculinity as a performance

Sky touched on a different part of masculinity: the need to perform. Within boarding schools, boys are often pitted against each other, measured by their ability to endure pain — be it physical, mental, or emotional. “If we are talking about raising boys, ‘resilience’ is the word that gets thrown around,” Sky says. “We teach boys to toughen up, to weather whatever life throws at them. But at what cost?”

This expectation of toughness is not unique to Malaysia, but it takes a distinct flavour in its cultural context. Malaysian boys grow up in a society where feelings are seen as a sign of weakness. Yet within these confines of boarding schools, they fight constant battles of yearning for validation but finding it only in displays of dominance and strength.

Sometimes, these displays of strength end up in harsh hazing rituals. Other times, they become ways of acting out that might end up in regrettable choices. In an environment where you are often required to fend for yourself — coupled with the need to put your masculinity on huge display — you could end up causing harm when you would not have otherwise. And when an oppressor is involved in this process, then one can see how easy it is to have bullying be an integral part of schooling life.

This is what sets Projek Kahar apart, its audacity to confront an uncomfortable truth: bullies are often victims first. Amir drives this point home. “It is easy to hate Kahar for what he has done. But if you peel back the layers, you see a boy who was never allowed to be weak, who was shaped by the same system he perpetuates.”

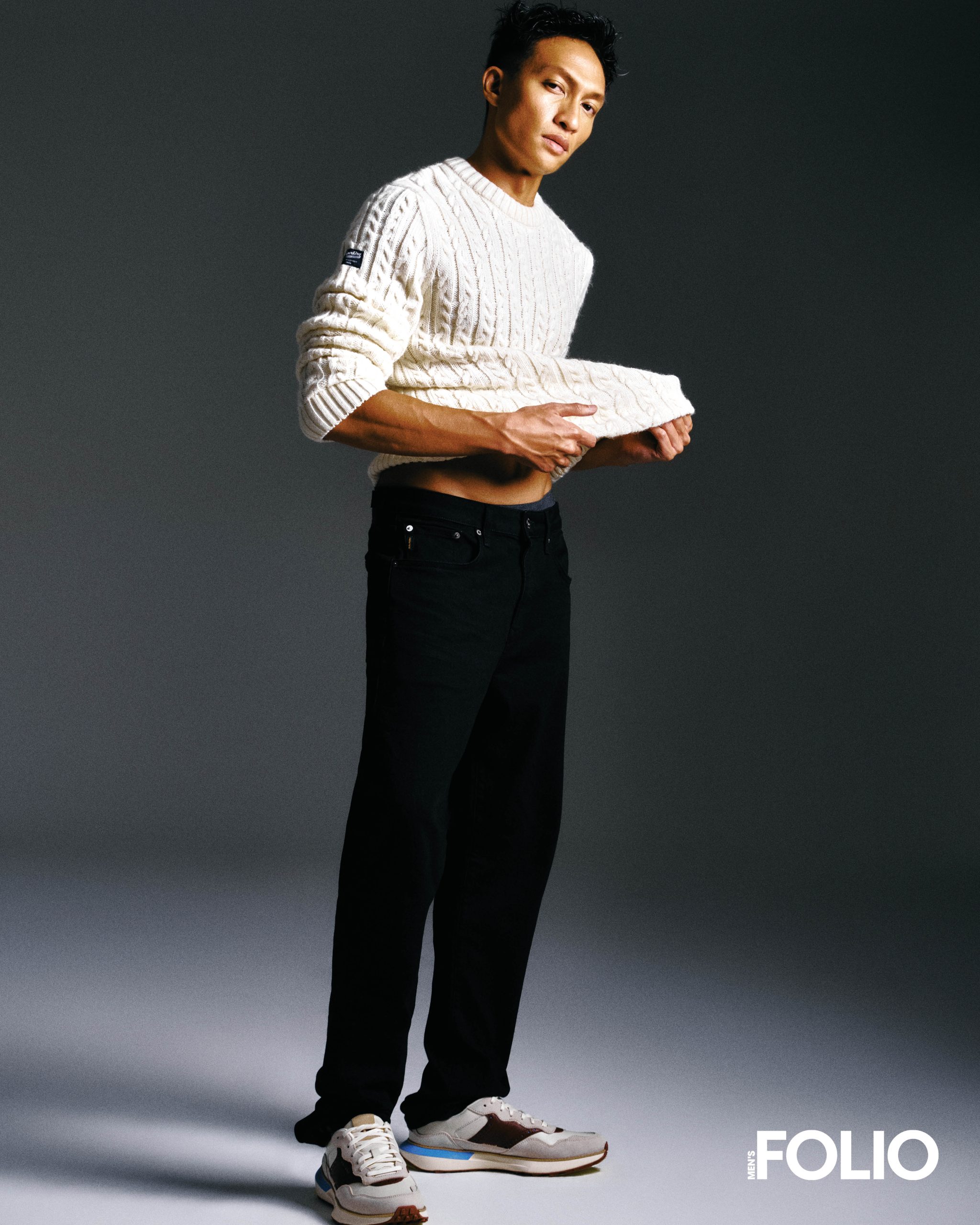

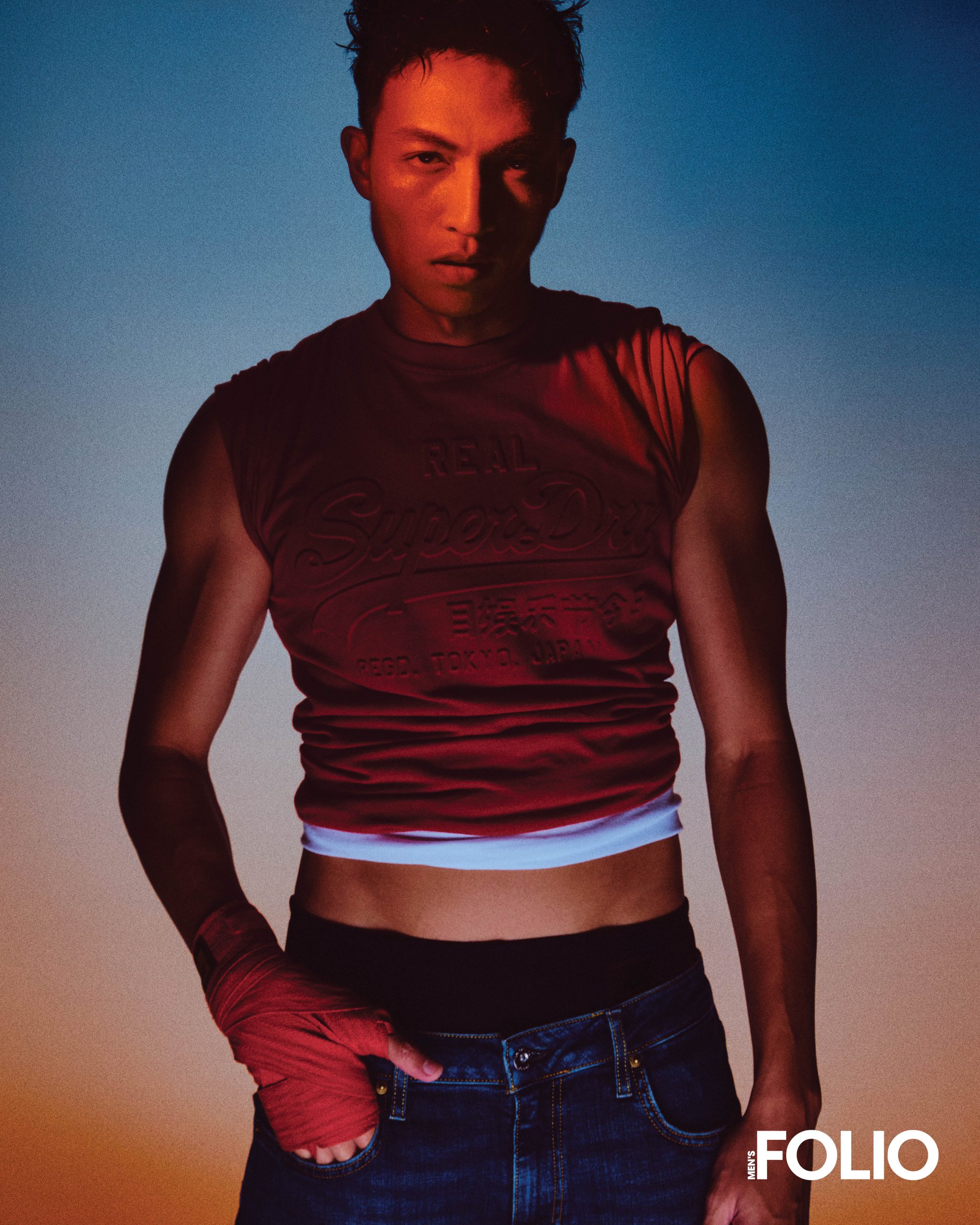

(On Sky Iskandar) Sweater, jeans, Superdry; Shoes, Cole Haan; Briefs, Stylist’s own

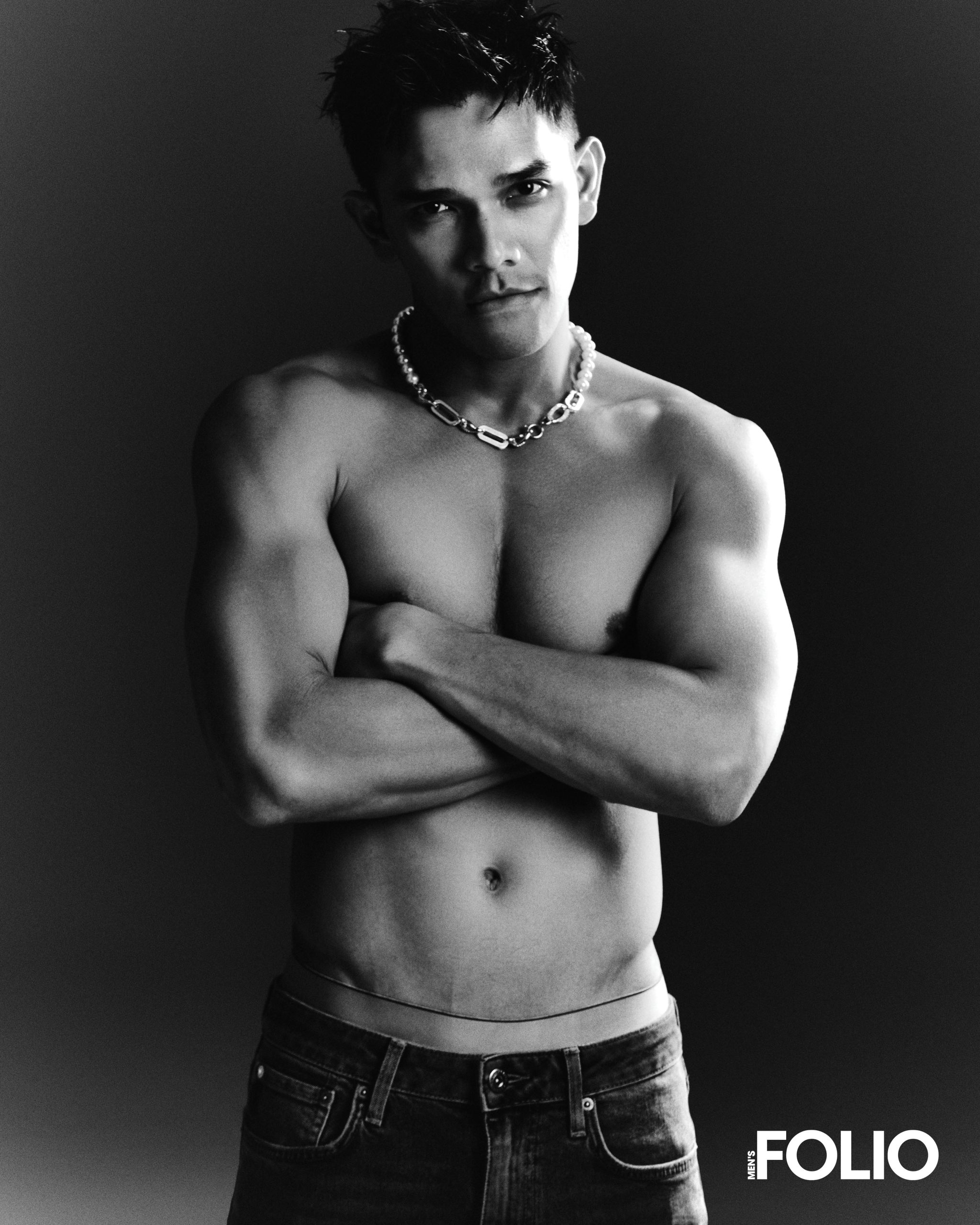

(On Aedy Ashraf) Jeans, Superdry; Necklace, Swarovski; Briefs, Stylist’s own

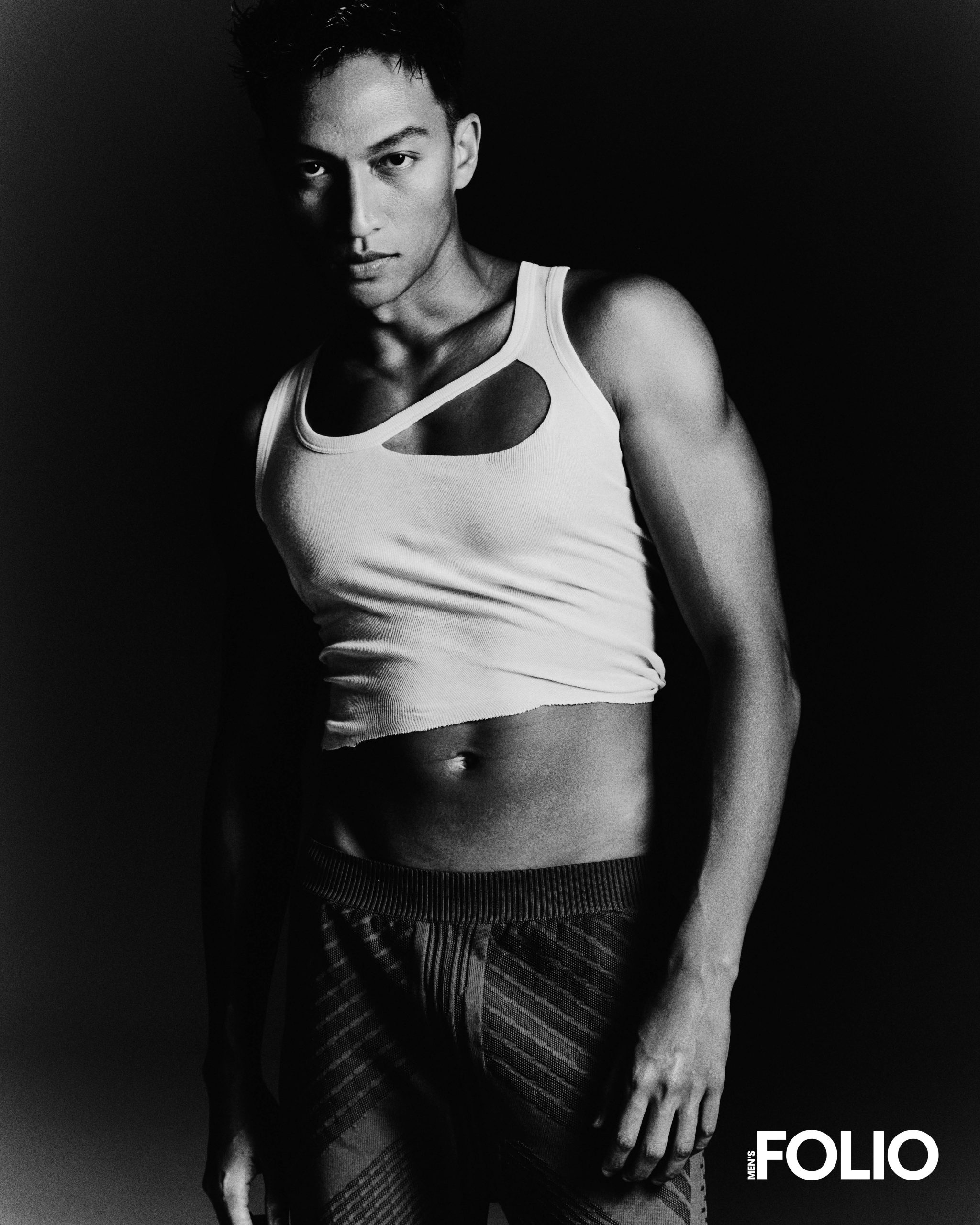

(On Sky Iskandar) Pants; Prada; Singlet, Stylist’s own

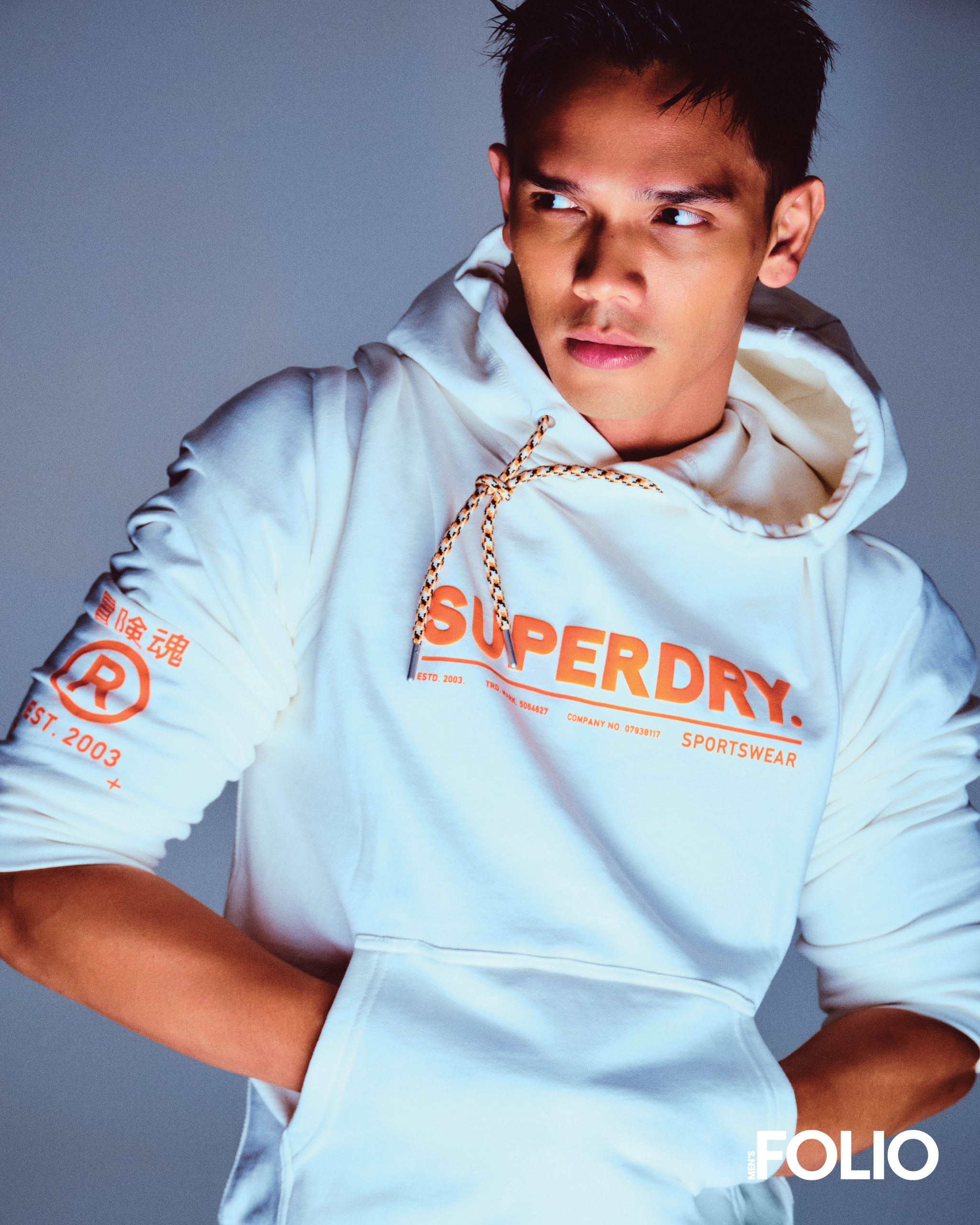

(On Aedy Ashraf) Hoodie sweater, all in Superdry

(On Sky Iskandar) T-shirts, jeans, Superdry; Briefs, bandage, Stylist’s own

Breaking the generational cycle

It is a sobering thought to think that this could be the way things will be through many more generations. After all, the system of bullying and forced masculinity has been part of the boarding school system for many generations before this. You could either choose to be ‘weak’ by these standards, or perpetuate a way of life that will not effect any meaningful change.

This perspective hits especially hard in Malaysia, where mental health conversations are still in their infancy, and boys are rarely given the tools to articulate their struggles. The film does not shy away from this failure — it forces the audience to reckon with the idea that toxic masculinity is not inherent; it is taught. And for young boys in the country, there are endless avenues where these lessons can come from.

Optimistically, it might also be the catalyst that encourages change in schools, which are often seen as the breeding grounds for toxic behaviour. Maybe it will trigger enough discomfort to generate more talk about the subject. Or maybe it will force us all to take a cold hard look on where we stand on the matter. Either way, we all have a role to play, both for the good and bad.

For Amir, slipping back into Kahar’s skin is his way of shedding light on the matter. “Kahar represents so many different people who have grown up navigating boyhood within our culture, going through the same experiences,” he reflects. “He is the embodiment of what they could have become, who they are still in the process of becoming and, in some ways, a haunting reminder of whom they must never turn out to be.”

Does this mean Amir is glorifying bullies? No. Bullying is always wrong, no matter the cause, but we cannot condemn the act on a blanket basis. We need to understand that there are nuances to this, and sometimes the bullies are helplessly driven down a path thanks to the nature and nurture of their lives.

Ultimately, the evolution of masculinity means navigating the many forces — expectations from family, society, and oneself. Projek Kahar offers a compelling portrait of how masculinity is not a fixed state, but an ongoing process of self-discovery, reckoning, and, at times, painful growth. It forces us to reconsider what it means to be a man in today’s world — whether we are breaking free from toxic cycles or trapped within them.

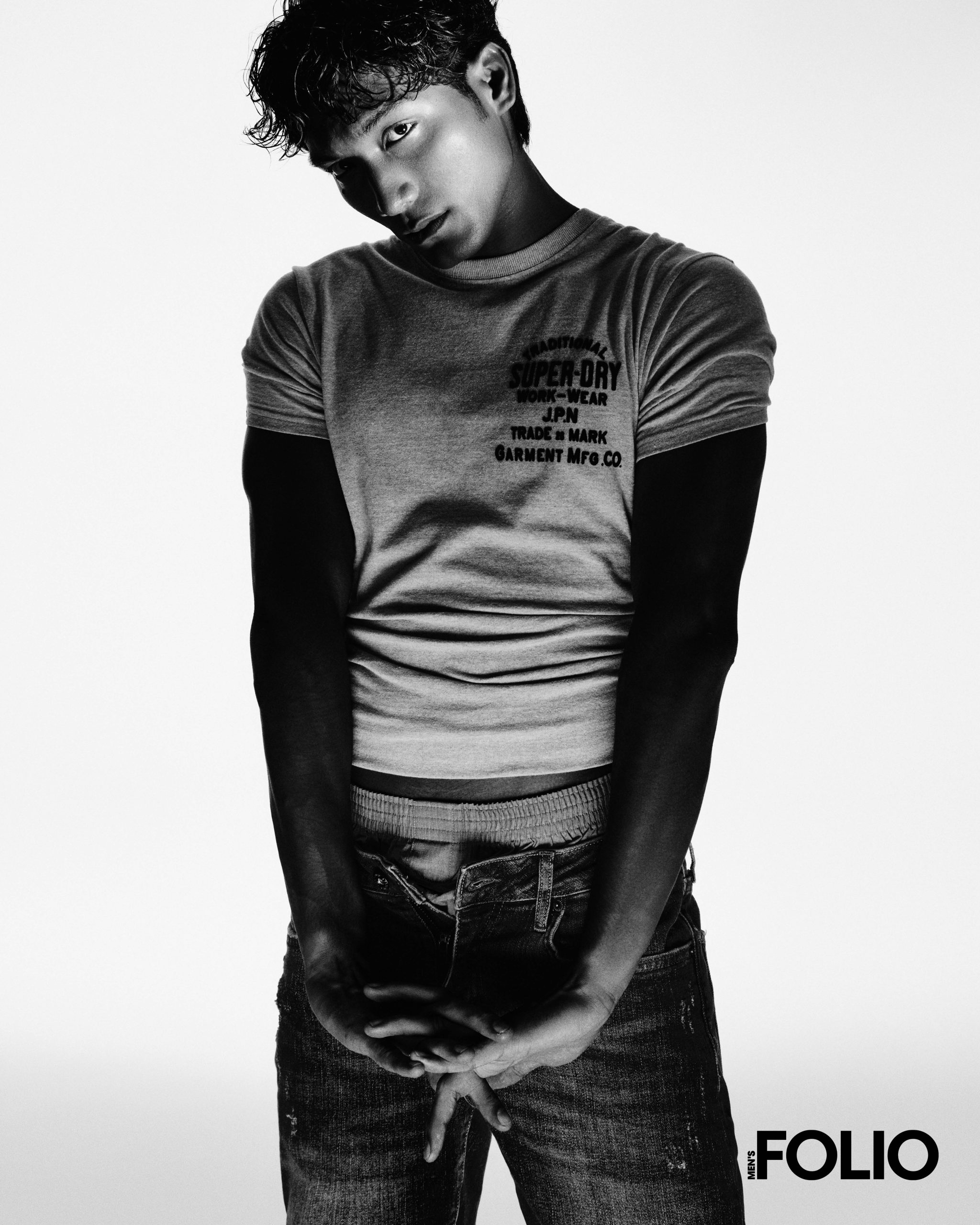

(On Amir Ahnaf) T-shirt, jeans, Superdry; Briefs, Stylist’s own

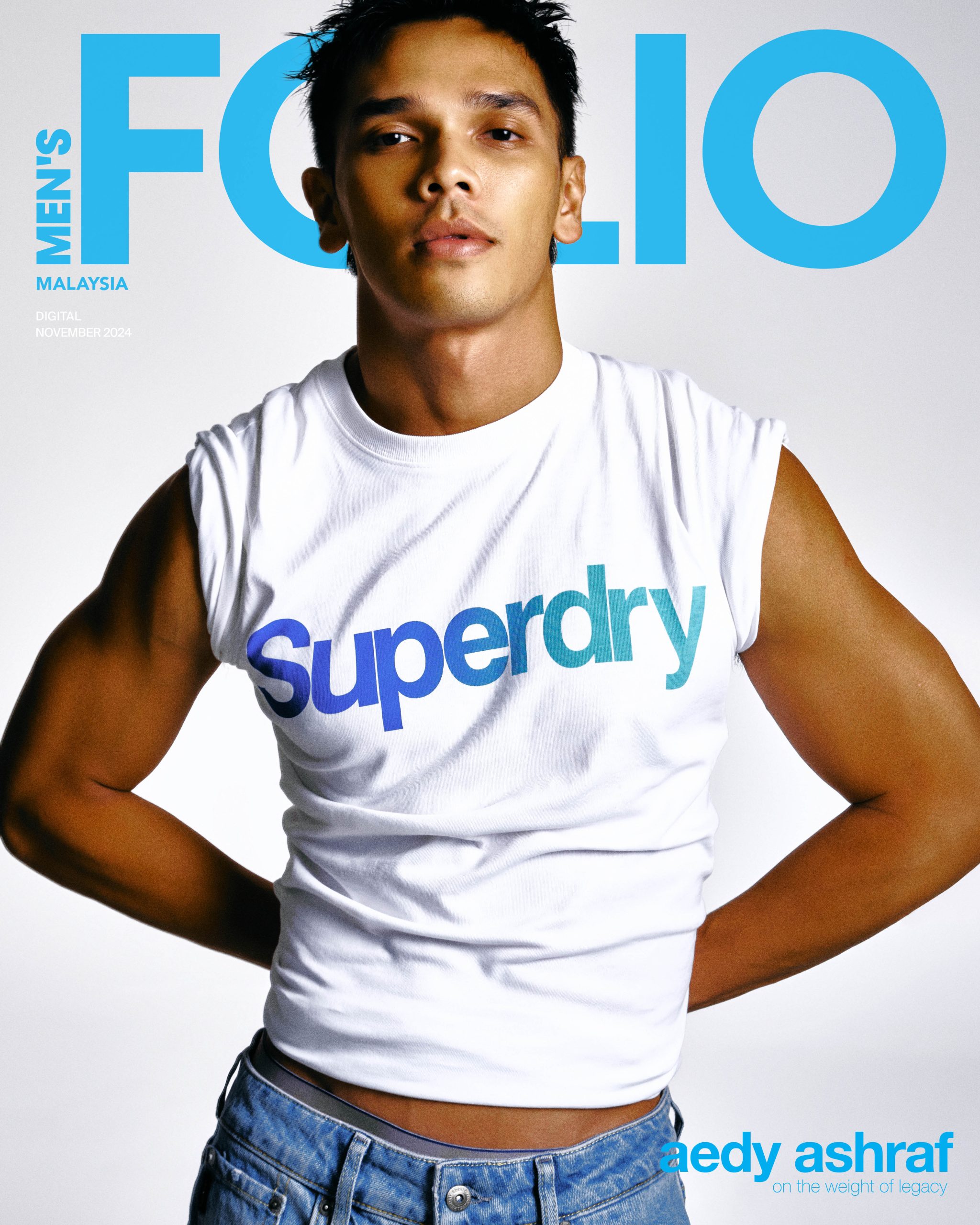

(On Aedy Ashraf) T-shirt, jeans, Superdry; Shoes, Cole Haan

(On Aedy Ashraf) Hoodie jacket, pants, Superdry; Shoes, Prada

(On Amir Ahnaf) Sweater, hoodie sweater (worn as an inner), jeans, all Superdry

Photography Chee Wei

Creative Direction and Styling Izwan Abdullah

Grooming Chu Fan

Hair Juno Ko

Production & Fashion Coordination Manfred Lu

Production & Styling Assistant Liew Hui Ying

Once you are done with this story, click here to catch up with our November 2024 issue.